Из-за различных неполадок или неожиданного отключения компьютера файловая система может быть повреждена. При обычном выключении все файловые системы монтируются только для чтения, а все не сохраненные данные записываются на диск.

Но если питание выключается неожиданно, часть данных теряется, и могут быть потерянны важные данные, что приведет к повреждению самой файловой системы. В этой статье мы рассмотрим как восстановить файловую систему fsck, для нескольких популярных файловых систем, а также поговорим о том, как происходит восстановление ext4.

Немного теории

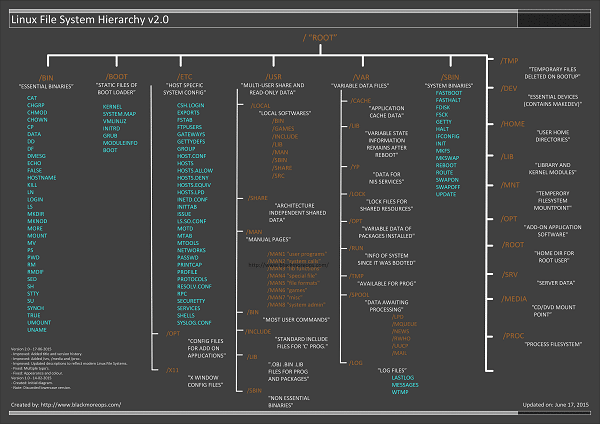

Как вы знаете файловая система содержит всю информацию обо всех хранимых на компьютере файлах. Это сами данные файлов и метаданные, которые управляют расположением и атрибутами файлов в файловой системе. Как я уже говорил, данные не сразу записываются на жесткий диск, а некоторое время находятся в оперативной памяти и при неожиданном выключении, за определенного стечения обстоятельств файловая система может быть повреждена.

Современные файловые системы делятся на два типа - журналируемые и нежурналируемые. Журналиуемые файловые системы записывают в лог все действия, которые собираются выполнить, а после выполнения стирают эти записи. Это позволяет очень быстро понять была ли файловая система повреждена. Но не сильно помогает при восстановлении. Чтобы восстановить файловую систему linux необходимо проверить каждый блок файловой системы и найти поврежденные сектора.

Для этих целей используется утилита fsck. По сути, это оболочка для других утилит, ориентированных на работу только с той или иной файловой системой, например, для fat одна утилита, а для ext4 совсем другая.

В большинстве систем для корневого раздела проверка fsck запускается автоматически, но это не касается других разделов, а также не сработает если вы отключили проверку.

Основы работы с fsck

В этой статье мы рассмотрим ручную работу с fsck. Возможно, вам понадобиться LiveCD носитель, чтобы запустить из него утилиту, если корневой раздел поврежден. Если же нет, то система сможет загрузиться в режим восстановления и вы будете использовать утилиту оттуда. Также вы можете запустить fsck в уже загруженной системе. Только для работы нужны права суперпользователя, поэтому выполняйте ее через sudo.

А теперь давайте рассмотрим сам синтаксис утилиты:

$ fsck [опции] [опции_файловой_системы] [раздел_диска]

Основные опции указывают способ поведения утилиты, оболочки fsck. Раздел диска - это файл устройства раздела в каталоге /dev, например, /dev/sda1 или /dev/sda2. Опции файловой системы специфичны для каждой отдельной утилиты проверки.

А теперь давайте рассмотрим самые полезные опции fsck:

- -l - не выполнять другой экземпляр fsck для этого жесткого диска, пока текущий не завершит работу. Для SSD параметр игнорируется;

- -t - задать типы файловых систем, которые нужно проверить. Необязательно указывать устройство, можно проверить несколько разделов одной командой, просто указав нужный тип файловой системы. Это может быть сама файловая система, например, ext4 или ее опции в формате opts=ro. Утилита просматривает все файловые системы, подключенные в fstab. Если задать еще и раздел то к нему будет применена проверка именно указанного типа, без автоопределения;

- -A - проверить все файловые системы из /etc/fstab. Вот тут применяются параметры проверки файловых систем, указанные в /etc/fstab, в том числе и приоритетность. В первую очередь проверяется корень. Обычно используется при старте системы;

- -C - показать прогресс проверки файловой системы;

- -M - не проверять, если файловая система смонтирована;

- -N - ничего не выполнять, показать, что проверка завершена успешно;

- -R - не проверять корневую файловую систему;

- -T - не показывать информацию об утилите;

- -V - максимально подробный вывод.

Это были глобальные опции утилиты. А теперь рассмотрим опции для работы с файловой системой, их меньше, но они будут более интересны:

- -a - во время проверки исправить все обнаруженные ошибки, без каких-либо вопросов. Опция устаревшая и ее использовать не рекомендуется;

- -n - выполнить только проверку файловой системы, ничего не исправлять;

- -r - спрашивать перед исправлением каждой ошибки, используется по умолчанию для файловых систем ext;

- -y - отвечает на все вопросы об исправлении ошибок утвердительно, можно сказать, что это эквивалент a.

- -c - найти и занести в черный список все битые блоки на жестком диске. Доступно только для ext3 и ext4;

- -f - принудительная проверка файловой системы, даже если по журналу она чистая;

- -b - задать адрес суперблока, если основной был поврежден;

- -p - еще один современный аналог опции -a, выполняет проверку и исправление автоматически. По сути, для этой цели можно использовать одну из трех опций: p, a, y.

Теперь мы все разобрали и вы готовы выполнять восстановление файловой системы linux. Перейдем к делу.

Как восстановить файловую систему в fsck

Допустим, вы уже загрузились в LiveCD систему или режим восстановления. Ну, одним словом, готовы к восстановлению ext4 или любой другой поврежденной ФС. Утилита уже установлена по умолчанию во всех дистрибутивах, так что устанавливать ничего не нужно.

Восстановление файловой системы

Если ваша файловая система находится на разделе с адресом /dev/sda1 выполните:

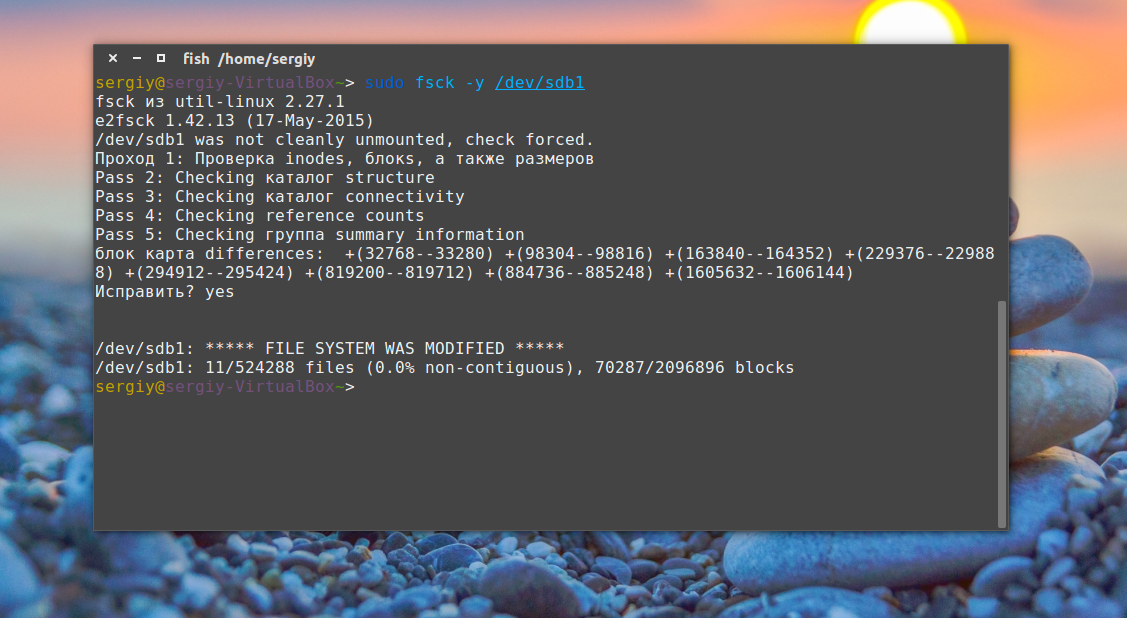

$ sudo fsck -y /dev/sda1

Опцию y указывать необязательно, но если этого не сделать утилита просто завалит вас вопросами, на которые нужно отвечать да.

Восстановление поврежденного суперблока

Обычно эта команда справляется со всеми повреждениями на ура. Но если вы сделали что-то серьезное и повредили суперблок, то тут fsck может не помочь. Суперблок - это начало файловой системы. Без него ничего работать не будет.

Но не спешите прощаться с вашими данными, все еще можно восстановить. С помощью такой команды смотрим куда были записаны резервные суперблоки:

$ sudo mkfs -t ext4 -n /dev/sda1

На самом деле эта команда создает новую файловую систему. Вместо ext4 подставьте ту файловую систему, в которую был отформатирован раздел, размер блока тоже должен совпадать иначе ничего не сработает. С опцией -n никаких изменений на диск не вноситься, а только выводится информация, в том числе о суперблоках.

Теперь у нас есть шесть резервных адресов суперблоков и мы можем попытаться восстановить файловую систему с помощью каждого из них, например:

$ sudo fsck -b 98304 /dev/sda1

После этого, скорее всего, вам удастся восстановить вашу файловую систему. Но рассмотрим еще пару примеров.

Проверка чистой файловой системы

Проверим файловую систему, даже если она чистая:

$ sudo fsck -fy /dev/sda1

Битые сектора

Или еще мы можем найти битые сектора и больше в них ничего не писать:

$ sudo fsck -c /dev/sda1

Установка файловой системы

Вы можете указать какую файловую систему нужно проверять на разделе, например:

$ sudo fsck -t ext4 /dev/sdb1

Проверка всех файловых систем

С помощью флага -A вы можете проверить все файловые системы, подключенные к компьютеру:

$ sudo fsck -A -y

Но такая команда сработает только в режиме восстановления, если корневой раздел и другие разделы уже примонтированы она выдаст ошибку. Но вы можете исключить корневой раздел из проверки добавив R:

$ sudo fsck -AR -y

Или исключить все примонтированные файловые системы:

$ sudo fsck -M -y

Также вы можете проверить не все файловые системы, а только ext4, для этого используйте такую комбинацию опций:

$ sudo fsck -A -t ext4 -y

Или можно также фильтровать по опциям монтирования в /etc/fstab, например, проверим файловые системы, которые монтируются только для чтения:

$ sudo fsck -A -t opts=ro

Проверка примонтированных файловых систем

Раньше я говорил что нельзя. Но если другого выхода нет, то можно, правда не рекомендуется. Для этого нужно сначала перемонтировать файловую систему в режим только для чтения. Например:

$ sudo mount -o remount,ro /dev/sdb1

А теперь проверка файловой системы fsck в принудительном режиме:

$ sudo fsck -fy /dev/sdb1

Просмотр информации

Если вы не хотите ничего исправлять, а только посмотреть информацию, используйте опцию -n:

$ sudo fsck -n /dev/sdb1

Выводы

Вот и все, теперь вы знаете как выполняется восстановление файловой системы ext4 или любой другой, поддерживаемой в linux fsck. Если у вас остались вопросы, спрашивайте в комментариях!